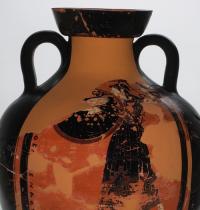

Athena in full armor between two Doric columns surmounted by roosters

Learn more about the object below

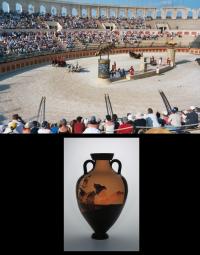

This amphora from the Yale collection receives its name from the most important civic and religious festival celebrated in ancient Athens, the Panathenaia. It was held annually in July, but every four years the festivities were especially spectacular and lasted more than a week. During these “Greater Panathenaias,” Athenians competed in musical performances, poetry recitations, and sporting events. The festival also included boat races in the city’s harbor and nighttime torch races, and culminated in a dazzling parade that led to the Acropolis. There, the revered cult statue of Athena Polias was ceremonially draped in a new, beautiful robe, painstakingly crafted by Athenian girls of noble birth.

Winners of athletic and equestrian events were awarded large quantities of valuable olive oil presented in amphorae with distinctive shapes and decoration. Panathenaic prize amphorae such as this one, have high shoulders and narrow bases, and standardized scenes showing, on one side, the goddess Athena with a Greek inscription reading “from the games at Athens,” and, on the other, a depiction of the sporting event for which the prize was given. They were always decorated in the black-figure technique, even after red-figure became the norm. It has been estimated that 1,400 amphorae were made for each Greater Panathenaia.

The four-horse chariot race, commemorated on the back of this prize amphora, was the most prestigious equestrian event in ancient Greece and Rome. The horses and vehicle were very expensive, and the race itself was fraught with danger. Team owners rarely raced themselves; instead, they hired professional chariot drivers, like the jockeys of today. Greek chariot races took place in hippodromes—wide open spaces almost a mile in length. Later Romans constructed oval arenas of the type illustrated here for their races. The ancient Athenian hippodrome has not yet been located and probably left little that could be identified archaeologically.

Prizes given to Panathenaic winners had not only symbolic importance (like the laurel wreaths of Olympia), but also real monetary value since the amphorae held costly oil from olive trees sacred to Athena. The winner of the chariot race received 140 amphorae, each holding 10.25 gallons, totaling some 1,435 gallons of oil. Victors may have used some of their oil for personal use—in cooking, in perfume preparation, or even in lamps—but the main worth of the prize was in its resale value, as Athena’s olive oil was in great demand and fetched a high price.

When looking at an object, whether a contemporary painting or a Classical Greek vase, it can be nearly impossible to distinguish the work of the original artist from areas that have been reconstructed by a conservator. When this amphora was recently conserved by Yale University Art Gallery staff, curators were faced with a challenging decision: how should they present the lost fragments? The orange-colored areas on this vessel are the result of curatorial choice. Rather than inpaint the missing fragments to reflect how the vessel may have originally looked, these areas have been left a terracotta color to demonstrate the lost information.

Label texts 1-4 by Pamela J. Russell, Ph. D., Andrew W. Mellon Coordinator of College Programs, Mead Art Museum, Amherst College.

Label text 5 by Rachel Beaupré, Andrew W. Mellon Assistant Curator, Mount Holyoke College Art Museum

Suggested readings:

Susan B. Matheson, "Panathenaic Amphorae by the Kleophrades Painter," Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Occassional Papers. Vol. 4 (1989), 95-122.

Jenifer Neils, Goddess and Polis: The Panathenaic Festival in Ancient Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.