Head of a woman

Learn more about the object below

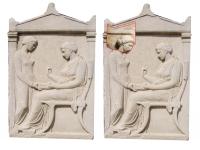

This marble relief sculpture is only a fragment of an original stele (grave marker). Can we reconstruct what is lost from just a woman’s face? We have no clothes, no name to hint at who she might be, but we see her hair is swept into a modest knot. She appears to stand in the corner of the frame and looks down at someone or something to our right. Consider the approximately contemporary Hegeso stele of a seated lady and her maid, illustrated at right. Perhaps the woman on the Mount Holyoke fragment is not the deceased at all, but her maidservant, faithful even in death.

A virtuous Athenian woman was expected to lead a private, almost cloistered life within her family’s oikos (household). Tombstones (stelae) offered a rare chance for survivors to proclaim a woman’s virtue or nobility in a public setting. Stelae also gave sons a chance to boast of their well-born mothers’ Athenian blood. The example of a stele fragment at right represented not only the wealth of the dead woman’s family, but also her own virtue as a good housewife, home in the women’s quarters where she belonged. If the Mount Holyoke fragment, like this stele, shows the deceased herself, her downcast gaze is suitably modest.

The living often join the dead on ancient Athenian tombstones. For example, a dead man’s stele might show him sitting peacefully with several members of his household; a little girl’s might have her playing with a pet bird; a young mother’s tombstone might depict her in labor, surrounded by attendants. In Athens’ famous Kerameikos cemetery, many of these scenes of lost life faced not inward, where the bereaved performed their rites, but toward the road, for passers-by to see. These scenes make the sense of loss more immediate, emphasizing the void the dead will leave in the life of city and household.

Label text by August Thomas, Museum Volunteer

Suggested readings:

Wendy E. Closterman, “Family Ideology and Family History: The Function of Funerary Markers in Attic Peribolos Tombs,” American Journal of Archaeology 111 (2007)

“The Hegeso Stele,” Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: A Global History, 13th edition. Wadsworth Publishing, 2008.

Page DuBois, “Greeks in the Museum,” Slaves and Other Objects. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.